Unless meaningful data comes out over the holidays, this will be the last full weekly for 2025, although we may publish a truncated version before the end of the year. We would like to wish all of our readers a happy and prosperous holiday season.

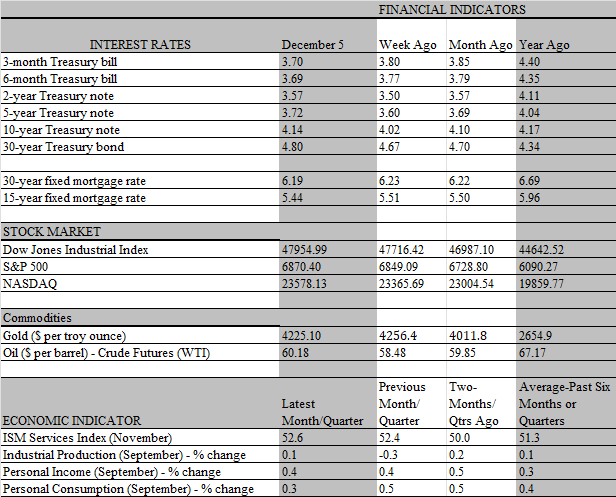

On the surface, the Fed has to be pleased with the bevy of reports released since the data spigot reopened last week. The quarter-point rate cut taken at the last policy meeting was met with some defiance among several officials, who worried more about aggravating inflation than supporting a softening job market. Since the meeting, three key economic reports have been released, throwing some light on the job market, inflation and consumer spending. All three have deep flaws and are widely viewed as degraded reflections of actual trends.

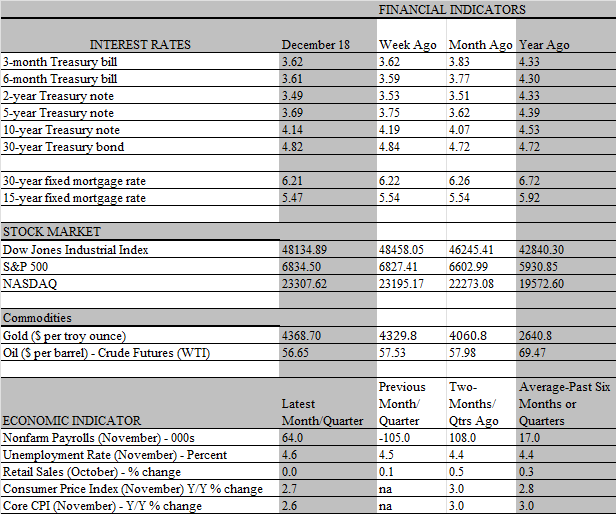

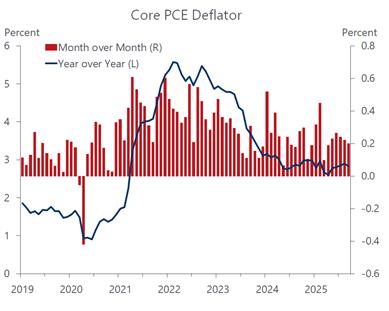

That said, the outcome delivers more validation than criticism of the Fed’s move. Indeed, the headline results suggest that the modest easing of policy might have been too mild. Recall that the Summary of Economic Projections (the SEP) presented at the meeting pegged the unemployment rate at 4.4 percent at the end of the year, and inflation at 3.0 percent for the overall Personal Consumption Deflator and 2.9 percent for the core PCE. The latest jobs and inflation reports indicate that those thresholds have already been violated, a month earlier than expected.

The unemployment rate in November leaped to 4.6 percent from 4.4 percent in September and the headline and core consumer price index rose 2.7 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, from a year ago. The November data for the PCE has not yet been released, but that gauge usually tracks a half percent or so below the CPI. This time, though, the gap should narrow as the PCE gives less weight to shelter costs, which was one of the biggest drags on the CPI in the November report for questionable reasons. Unsurprisingly, the tame inflation reading did little to convince Fed watchers that another rate cut was coming at the January meeting. As of Friday morning, traders priced in only a 20 percent chance the Fed would pull the rate trigger next month according to the CME’s FedWatch rate tool. Meanwhile, the 2-year Treasury yield, which is heavily influenced by Fed rate expectations, ended the week almost spot-on with where it stood after the first of the week’s three reports was released on Tuesday.

The market’s skepticism that the reports would move the needle with the Fed echoes the deep skepticism over the reliability of the data. Most important, data collection did not begin until mid-November after the 43-day government shutdown ended. That, in turn, prevented the BLS from gathering price information for October or conducting the usual survey of households on their employment status for that month. This left a big void of information that precluded estimating a month over month change in prices for November and a tally of the unemployment rate for October. What’s more, the October void and the late start of the collection process imparts a downward bias to the November results. Unfortunately, that distortion will infect a lot of data for the next several months.

In the case of the CPI, the BLS assumed that there was no change in rents in October which lowered the base for the November increase and imparted a downward bias to the year-over-year calculation. The annual increase in shelter costs fell to 3.0 percent in November from 3.6 percent in September/October, the sharpest deceleration since the tail-end of the housing bust in January 2010. Housing costs have an outsized influence on the consumer price index, accounting for 40 percent of the core CPI and about a third of the overall index. To be fair, housing costs have been cooling for some time as signaled by the years-long deceleration in rents tracked by Zillow and other industry sources. But the plunge in shelter costs in the November CPI report overstates the slowdown.

That said, inflation pressures should continue to ease in 2026, as its main drivers are fading. Goods prices linked to imports will likely get a bump early next year, as the final leg of the 2025 tariffs are passed through to consumers. But the key driver of service prices, labor costs, is expected to wane as job growth continues to slow. That trend is firmly underway. Overall, the November jobs report was a mixed bag. Total payrolls slumped badly, thanks to a huge drop in Federal employment as government workers who took deferred resignations earlier in the year finally fell off of the payroll ledger. But the private sector took on a decent number of workers, expanding payrolls by 65 thousand in November and an average of 75 thousand over the past three months. That’s actually a step up from the previous three months, which saw an average gain of only 13 thousand a month.

But the slowdown in private payrolls from an average of over 100 thousand over the first five months of the year is palpable, and the gains are becoming increasingly confined to a few industries. Indeed, health services and private education accounted for all of the increase in private payrolls and then some since April. The slowing payroll growth in most other industries reflects the no hiring strategy being adopted by the business community to restrain costs and correct for the over-hiring during the early post-pandemic years. Importantly, the hiring pullback is undermining labor’s bargaining power, as wage growth is slowing significantly. The 3.5 percent increase in average hourly earnings in November from a year ago is the slimmest gain since 2021.

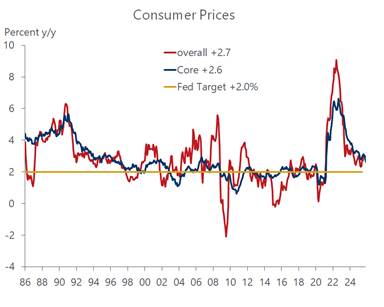

While the decent increase in private payrolls added a positive hue to the jobs report, the headlines featured its most glaring weakness – an increase in the unemployment rate to 4.6 percent, marking the highest level since 2021. Simply put, the increase in job seekers exceeded the increase in people finding jobs. For a labor force that has been squeezed by the immigration crackdown, deportations and retirements, the question is: Where are these job searches coming from? One answer is that people are reentering the labor force in droves. In November the number of reentrants to the labor force jumped to the highest level in more than a decade, extending a trend underway since the summer.

The reasons for the sudden upsurge in people reentering the job market is unclear. Some may be ex federal workers who dropped out after receiving their extended resignation packages earlier in the year and are now tapped out, opting to seek a new paycheck in the private sector. More likely is that an increasing swath of the population is struggling to make ends meet, reflecting high prices, big debts and eroded pandemic-era savings. Interestingly, it does not seem that the influx is being helped by people coming out of retirement. The labor force participation rate for people 55 and over fell to under 38 percent for the first time since 2006. That’s not surprising, as the older cohort owns most homes and financial assets that have appreciated mightily over the years, which hugely brightened the golden years of this segment of the population.